A Real World Example of the 70/30 Venture Capital Rule

Guest Author, Henry Kressel, Emeritus Managing Partner, Warburg Pincus

In a recent post, “The Venture Capital 70/30 Rule,” I described a rule that most VCs use to decide whether to invest in your venture. To summarize it, most VCs say that about 70% of their decisions concern the CEO and the team, and 30% the venture concept. This approach to decision-making stems from the VC belief that great teams will be able to build great ventures, and mediocre teams will never build great ventures. Also, if the venture concept turns out not to work, a great team might manage to pivot to discover an alternative venture concept, while a mediocre team never will.

Henry Kressel, emeritus managing director at Warburg Pincus and a co-author of our book “If You Really Want to Change the World: A Guide to Creating, Building, and Sustaining Breakthrough Ventures, Harvard Press” offers the example below.

As Norman pointed out in his advice to venture startup teams seeking investment, 70% of their success is due to the credibility established by the team and 30% to the quality of the proposed business plan. After many years of successful investing, I wholeheartedly agree with this comment.

Let me take this opportunity to discuss one of my most successful startup investments and illustrate the wisdom of this advice.

The Nova Corporation Startup

In 1991, a startup, Nova Corporation, entered a rapidly growing credit card processing industry wholly dominated by big banks. The startup faced immense technological and marketing challenges. Nova succeeded brilliantly, and the key lessons learned are of universal value. Hence, my choice here.

Here was the Nova Corporation value proposition:

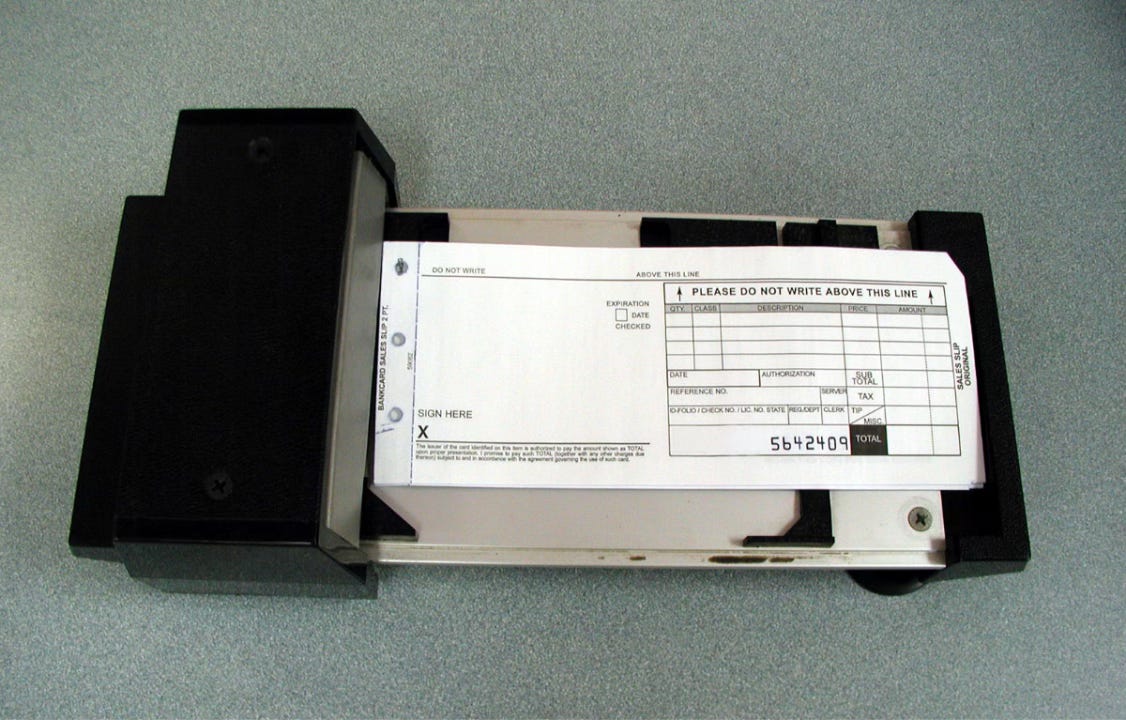

We now take for granted the smooth process of purchasing with a credit card. You insert or swipe your card in a special little box on the merchant counter, and the purchase is made. The purchase authorization is done quickly and seamlessly.

This was not the case in the early 1990s when credit card authorization was done mainly by merchants calling the authorizing bank call center for approval. Only the large merchants had costly terminals that required manual entry of the customer card number and as much as half a minute for the authorization to come through. In effect, credit card utilization was a tedious process, severely limiting credit card use for small merchants. Even supermarkets were late in using credit cards.

A group of eleven professionals and executives employed by major banks got together under the leadership of a senior manager to enter the credit card processing business. They would use a new technology that they believed would make the card processing business less expensive and highly accessible to small merchants. They left their employer and, using their own funds, developed a business plan and began technology development.

A business broker in Atlanta suggested that Warburg Pincus could be a funder for the venture, and this is how I met the team in my office.

They came in extremely well-prepared. The eleven had different expertise—technology, sales, and service development—and two had extensive management experience. Every question that I had about the startup's challenges was answered with realistic answers. I was particularly impressed by the technology team, whose approach promised a major reduction in the time and cost of validating credit cards, greatly improving the prospects of expanding the credit card market by allowing small merchants to offer credit card payments.

The proposed new technology was impressive on two counts. First, the team devised a data processing technology that did not require costly mainframes but used less costly small computers—an important benefit in getting the company launched economically. The second important feature is that the merchant terminal could be delivered for well under $1000 dollars. The team believed that they could validate authorization in 9 seconds or less.

The company was able to grow its customer base economically and deliver superior service to small merchants. Ultimately, in addition to superior technology, the company developed a deeply effective marketing strategy leveraging regional bank marketing partnerships and acquiring merchant customers through acquisitions. The speed of growth and profitability were outstanding.

This first meeting impressed me on two counts.

First, a large market was available with the right execution.

Second, this team was of exceptional quality and credibility.

They left the meeting with an assignment. I wanted to see more technology work to substantiate some of the claims. On my side, I promised due diligence toward an investment possibility.

I conducted extensive due diligence with organizations such as Mastercard and communications specialists. All was positive. Meanwhile, their technology work substantiated their claims. They also built a detailed business plan showing that $30 million would take them to cash flow breakeven.

Warburg Pincus invested in the company based on the completion of the tasks we had agreed to, and Nova became a new company in an industry dominated by giants. It quickly rose in importance.

The performance of the company was outstanding, and it became a leader in the small merchant processing business. In 1999, after an IPO, the company was the processor for 355,000 merchants (10.4% of US merchants) with a volume of $40 billion and a 7% market share.) Nova was the second largest processor by merchant number and fourth in terms of credit card volume processed.

Warburg Pincus turned its $30 million into a $300 million return.

The lesson to take away from this example is clear: start with an experienced and talented team that covers all the key bases of the investment risk. Then, relentlessly focus on execution. But without the first, execution with mediocre talent will fail.

Guest author Henry Kressel,

and

Your Venture Coach,

Norman

Nice. As you always say, take it to the limit. 0 team X 100 concept = 0 results. For sure if the team can't do it, it starts as a zero. If they can do it, they are going in the right direction, and they know how to proceed, the odds go way up. Of course the odds of a poor team having a good, unique, compelling, and defensible value proposition are always very low. They always say, do, or miss something fundamental.