How To Create and Launch Breakthrough Technology Ventures from Research Laboratories: Personal Examples

Part III, The Last of This Series

In the last two posts, I described the five key groups that were the driving force behind the creation of over 70 ventures. In this final post of this series, I give personal examples of why these groups were essential to our success.

The Ventures Group: To briefly restate from Post II, the Ventures Group was composed of exceptional individuals I had recruited. Their expertise combined all three areas: markets, technology, and venture creation. The Ventures Group's primary task was to identify breakthrough technology venture concepts and assist in their creation.

When I first came to the Institute, I was recruited as a VP, responsible for all commercial business development. (Government business development was still the exclusive domain of the technology divisions.) There was no Ventures Group at that time. My goal then was to generate commercial revenue for every division, as well as develop ventures and royalties. The research divisions were most concerned that my team generate commercial revenue, since it would have an immediate effect on their own metrics for success. In contrast, developing ventures was considered much less important. In fact, since ventures could take years to make a financial impact, this part of my role was considered by many as a drain on the precious profitability of the Institute.

After working several months in this role, I had a private conversation with Dennis Beatrice, a Vice President, great friend, and one of the wisest people I have ever known. I discussed with him how torn I was in my role.

I told Dennis that my division was totally dedicated to generating commercial revenue, and there was little to no time for venture creation. I also told him that I would need to make dramatic changes to my team, which was made up of business development people who had previously worked in the divisions and whom the CEO had moved into my division. Almost every member of the team made it clear to me that they preferred to have the position that had been given to me. The team became dysfunctional, and I had a choice: either let most or all of them go and start again, or do something new.

Dennis gave me some of the best advice of my life.

He said, “Norman, what do you really love to do in life?” I responded that what I really loved and wanted to focus on was to create ventures - as I had done before at RCA Labs. And that, as I mentioned above, I was struggling to do this in my new role. He then said, “Norman, if that is what you love, why don’t you do that?” My answer was that there was no separate venture group, and there would be no budget for it. He said, “Do what you love, Norman. Make it happen.” I can’t tell you the sense of relief that flowed over me. I knew immediately it was the right decision. That evening, I told my wife what I wanted to do, and she was entirely supportive. Only years later did she tell me how much it had, in fact, worried her.

The next day, I went to our CEO and said I would like to no longer lead the Commercial Business Development group. I told him that “I would like to create a Ventures Group, separate and distinct from the Commercial Business Development group, and start it with only me and an assistant. I would need a modest budget and have an exclusive focus on helping create and build ventures. I would not add any people to my team until we proved that we were creating value. If this didn’t work, I would leave.”

He agreed, and the Ventures Group was formed. I have no doubt that creating this group and having the ability to exclusively focus on creating ventures was essential to our success.

The Vanguard Teams: As I wrote in Post I, the Vanguard Teams were composed of enthusiastic and passionate entrepreneurs, scientists, and strategic advisors who worked together to conceive and develop an initial breakthrough technology venture concept. These teams were the basis for every venture we started.

The decision not to compel team members to join the venture turned out to be a very good decision. It is difficult to leave a role in research and take a position in a company building a product. If they stayed, we would still get their crucial input into creating and building the company and would also give them a small stake in the company.

As a result of building these teams, we had world-class team members working together to create and build ventures in robotics, biotech, communications, AI, and more.

The Venture Advisory Group: When we first created the Ventures Group, we had great depth in technology and very little experience in venture capital and venture creation. So, we asked highly accomplished individuals from outside the Institute to join the Venture Advisory Group. This group worked with us on a regular basis, often a few days a week, helping us every step of the way. Several of these individuals were venture capitalists who also had strong technology backgrounds. Four of them, in particular, David Liddle, Gary Morgenthaler, Yogen Dalal, and David Ladd, helped us in every aspect of creating ventures, from strategy to execution.

Learning how to create and build ventures is not a science that can be learned by reading a book or taking a class. You can’t learn to create and build ventures without “living it,” any more than you can learn to play the violin without playing it. These four individuals mentored our teams and us as we began building ventures.

I have to laugh about a comment that David Liddle once made to me in the early days about helping my team learn to create and build ventures. When we first began, he said, “Norman, helping your team create ventures is like giving rifles to the band.” I didn’t know whether to laugh or be offended. But in truth, David never meant to offend. He was always just forthright and truthful. David was so knowledgeable and important to me that I often called him “My Sensei” and sometimes, when times were difficult, “My Rabbi.” He, in turn, would often call me “Grasshopper.”

I owe deep gratitude to these members of our Venture Advisory Group: David Liddle, Gary Morgenthaler, Yogen Dalal, and David Ladd. They were the true founders of our venture strategy.

The Venture Capital Forum: The Venture Capital Forum became a crucial part of our venture creation process. Unlike the Venture Advisory Board, the Venture Capital Forum would only meet once a quarter or so. The members were not only great investors; they were currently investing in the technology and market areas of our ventures. As I mentioned in Post II, they gave us their thoughts and critiques at the Forum, but they also solved a critical problem that I didn’t expect—our team’s credibility.

Let me explain:

When we formed venture teams, and they began to develop their value proposition and deck, members of my Ventures Group team might give them advice on virtually any aspect: the market concept, the go-to-market strategy, the revenue model, and more. For many of those Vanguard teams, their reaction was: “No, we don’t agree with your advice. We have worked longer and harder on this venture than you have. We are deeply knowledgeable in science and engineering. We know better than you. Why should we follow your advice?”

Even the advice of our Venture Advisory Group wasn’t enough for them to believe that our advice was good and credible. But when we presented the ventures to the Venture Capital Forum and asked them their thoughts and whether they would consider investing, the venture teams listened. And when the Venture Capital Forum advice was often the same as the advice my team gave, the issues as to our credibility disappeared.

The Venture Capital Forum was always a high point for our venture presentations. Teams worked months to prepare for those 15 - 30 minutes of presentation. And at the end, the VCs in the meeting would not just be asked for a “Thumbs Up,” or “Thumbs Down.” They would have 10 - 15 minutes to explain why they liked or disliked the venture. Everyone on the teams always wanted to hear these comments. Beyond that, it was great practice for the future time at which they were to be launched and raise investor funding.

The Commercialization Board (CB): As I mentioned in Post II, The CB was exclusively made up of employees of the Institute and provided the resources for our venture teams, including retainer agreements, expenses for researchers, equipment, and more. The CB members were highly knowledgeable about all aspects of venture creation and were not just deciding how much to invest or whether to invest. They were motivated to help the venture continue its development. The CFO would provide insights relating to finance, the General Counsel would provide insights into legal and IP issues, and the Technology Division VPs would provide insights into the capabilities of the technology. Our goal was to help the venture, not just decide if it was at a stage to pass a “gate.”

Most Commercialization Board meetings were collegial, and the board's insights were valuable to the emerging venture. One meeting stands out to me, though, above all others, as having been difficult and contentious. We were reviewing a venture whose concept seemed somewhat crazy, though I was both an advocate and supportive of creating the venture. As I said in this Post, many of the greatest ventures start off by seeming crazy.

The Entrepreneur-In-Residence (EIR), who helped conceive of the venture and was speaking and hoping to be the CEO, made claims that some board members felt were outrageous. His presentation material was slick, and his style was breezy. He clearly was a great marketer, but some of the more conservative board members weren’t sure he’d be a great CEO.

At the end of the presentation, as usual, the EIR and team were asked to leave, and the board convened.

I asked everyone on the board to give their thoughts and, after that discussion, for their vote. One of the board members felt so strongly against the venture that he voted to “blackball.” This had never happened before. Four others voted to abstain. This number of abstentions, again, had never happened before. Four board members, including myself and the CEO, voted positively. We didn’t use “majority rule,” so as the Chair, I made the final decision.

I decided we would fund the venture.

And this is how Siri was born.

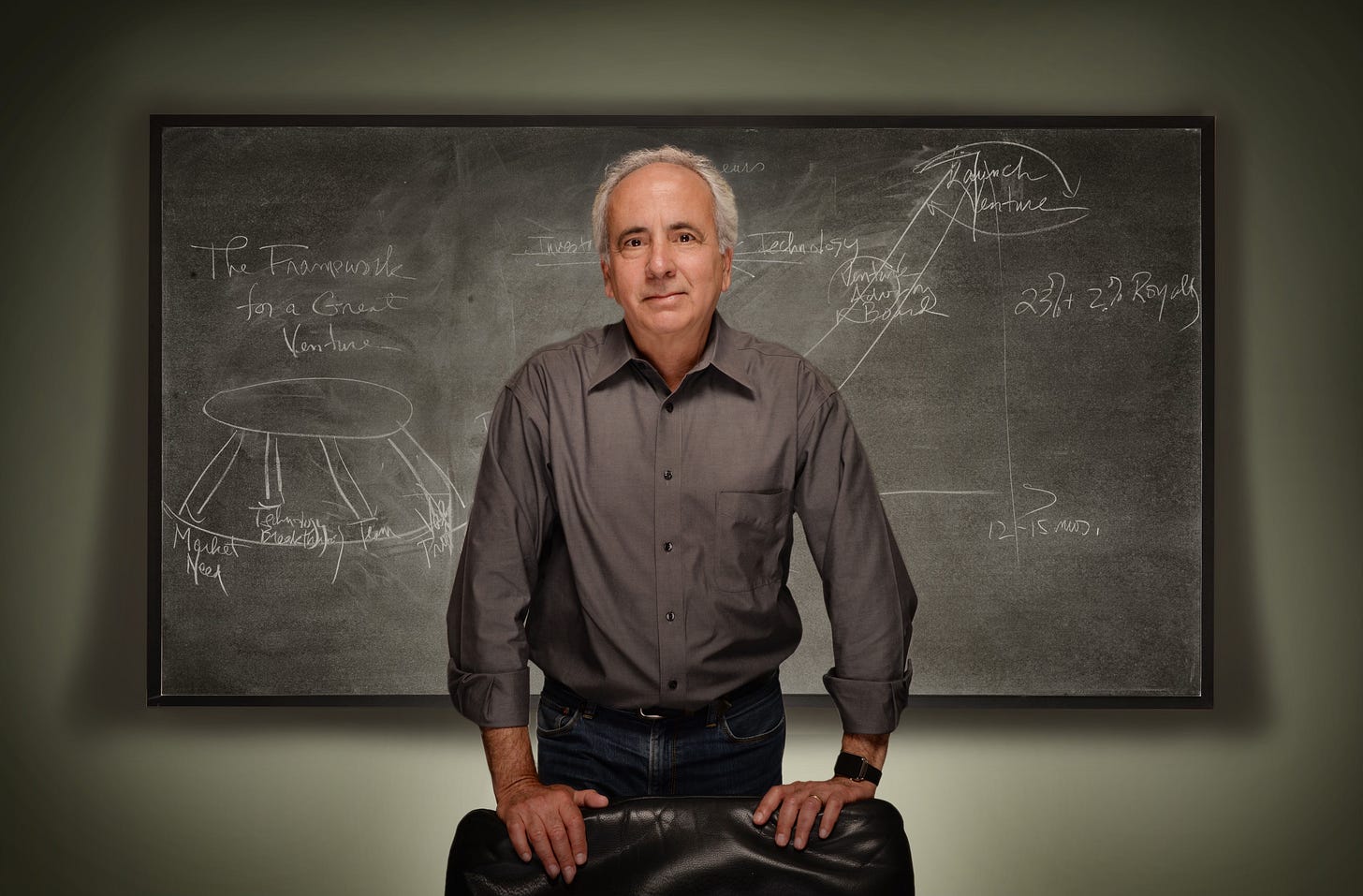

Your Venture Coach,

Norman

Amazing story, Norman! Thanks for sharing!