Most startups fail to give investors a compelling demo

And yet the demo is one of their most crucial tasks

Why do demos to investors fail? No, it isn’t because of Murphy’s Law. Demos can fail for many unfortunate reasons, like losing internet connectivity, or having an app crash, or having a server go offline. But great investors will forgive this.

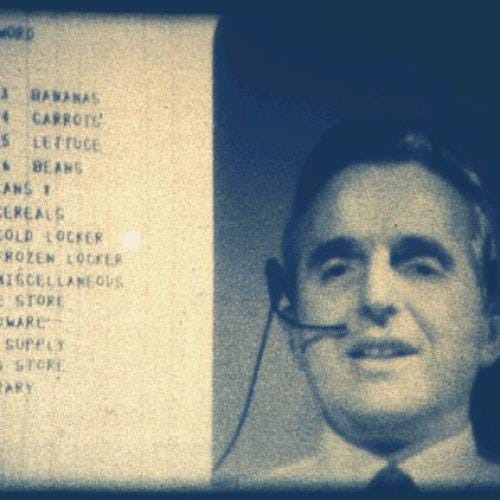

Perhaps one of the most famous demos of all time - called the Mother of All Demos - is a good example. Doug Engelbart was demonstrating the first internet transmission - on October 29, 1969. There’s a powerful story that highlights how a demo can fail for unfortunate reasons and still succeed.

Here is an image of some of the intended transmissions:

But before transmitting this, a connection had to be made. Leonard Kleinrock at UCLA sent a message from UCLA to Bill Duvall at Doug Engelbart’s lab at SRI, attempting to type the word LOGIN. The first characters sent were LO and then the network crashed before the additional letters GIN could be added. In truth, “LO” was prescient - think of “Lo, and behold.”

This failure didn’t matter. In fact, it was impressive. The capability of internet transmission was demonstrated.

In addition, most investors enjoy seeing demo difficulties. They like seeing how the founders react and recover from the event. It is very telling as to how the team will function when these types of events occur when the product is live.

The most compelling, exciting, and important part of the discussion with investors comes with the demonstration. After all, the demo brings to life the startup’s solution and allows for a deep understanding of the power of a transformational idea.

So what else can go wrong?

1. You choose the wrong demo.

When venture capitalists are considering investing in your venture, they need to understand your risks and how you are going to mitigate them. For example, when I created a venture with deep technology, often the risk is whether the technology will work well.

The most important function of the demo is to show that the risks are mitigated. Anything else is a waste of your time and energy.

For example when Siri was seeking investment, there were two crucial venture risks: the first risk was technology - could Siri do these things?

recognize the words in a consumer’s spoken query,

translate them to text,

recognize the intent of the query,

call upon the applications that could provide the response to the query,

fill the right information into the applications,

get the response from the applications,

organize the response to the consumer into a text sentence,

translate the text into speech,

and talk back to the consumer.

At the time, performing all the tasks was a difficult problem. Most difficult were steps 3 - 7. And so we focused our initial demo with text alone, assuming that the VCs would understand that the other elements were not risky.

The second venture risk was whether Siri would be sufficiently differentiated from Google. So we demoed a text query to Siri and showed how it was answered immediately with a text answer. We then gave the same query to Google, and showed how the response was a set of links, and much more time consuming and difficult to interpret.

Some advice to you: it is highly impressive to investors when you demonstrate your solution side by side with your top competitor’s solution and show how yours is superior!

2. You choose the wrong presenter.

The CEO is the best choice to be the presenter - since it is the CEO’s chance to demonstrate her overall understanding of the product and all its capabilities. It’s also fine to have the CEO hand off the demo to different team members through parts of the demo. But handing the demo over to the CTO, as one example, can be a mistake if the CTO is not business-minded and/or not a great presenter.

Whoever is presenting the product needs to make sure their narrative is consistent with the overall pitch, and that the demo demonstrates the value described in the pitch, not their personal pride in the implementation or the glorification of computer science.

3. You do a poor job of framing the demo story.

The demo needs to be a powerful way to give the investor an understanding of your product. Remarkably, I’ve seen countless demos where the investors didn’t understand more about the product after the demo than before. Beyond that, it left them somewhat confused as to the points the presenter was trying to make. Don’t assume the investors understand what they were supposed to see and why it was impressive. You need to tell them!

Here’s how to frame the demo story:

Before the demo, explain to the investors what they’re about to see and why you are showing it to them. Tell them about the problems that you solved and that you are demonstrating the solutions. Tell them about how the product is differentiated from the competition. Show how your product works compared to the competition.

Give the demo. (We describe many means of giving the demo in the next section.)

After the demo, explain again what the investor saw, what you did in the demo that was new and compelling, and how it solved the hard problems you described before the demo. Ask them if they understood what you demonstrated and if they agreed that you demonstrated the solutions to the important problems.

Discuss how your competitors solved the problem.

Ask your investors if they understood the difference between what you did and what the competition did. Ask them if it was a powerful and compelling solution.

4. The presenters fail to choose the best demo approach.

What if the product is not complete? At SRI we suffered this problem for almost every venture we started, because we were developing deep technology ventures, and part of the purpose of the VC investment was to sufficiently advance the technology development so that we could build the product.

There are at least five ways to give a powerful demo, depending on the state of the product development. Here they are in increasing difficulty but also increasing effectiveness. Choose the most effective demo type!

The canned demo

The canned demo could be a video, a storyboard, or a series of wireframes that step by step enable the investor to see the capabilities of the product and the user experience, as well as to compare it to the competition. Like a presentation, the script doesn’t vary.

Since this is a canned demo, it doesn’t show live that you solved the hard problems, so it’s not very effective. But at least it indicates more visually how you are thinking about the solution.

When Lyft was seeking its seed funding, a canned demo would have been fine. Investors could see how it enabled customers to see the locations of available drivers, the cost, the time to reach them and their destination, and more. The power of the Lyft venture came from creating a new experience. A canned Lyft demo would give that experience effectively.

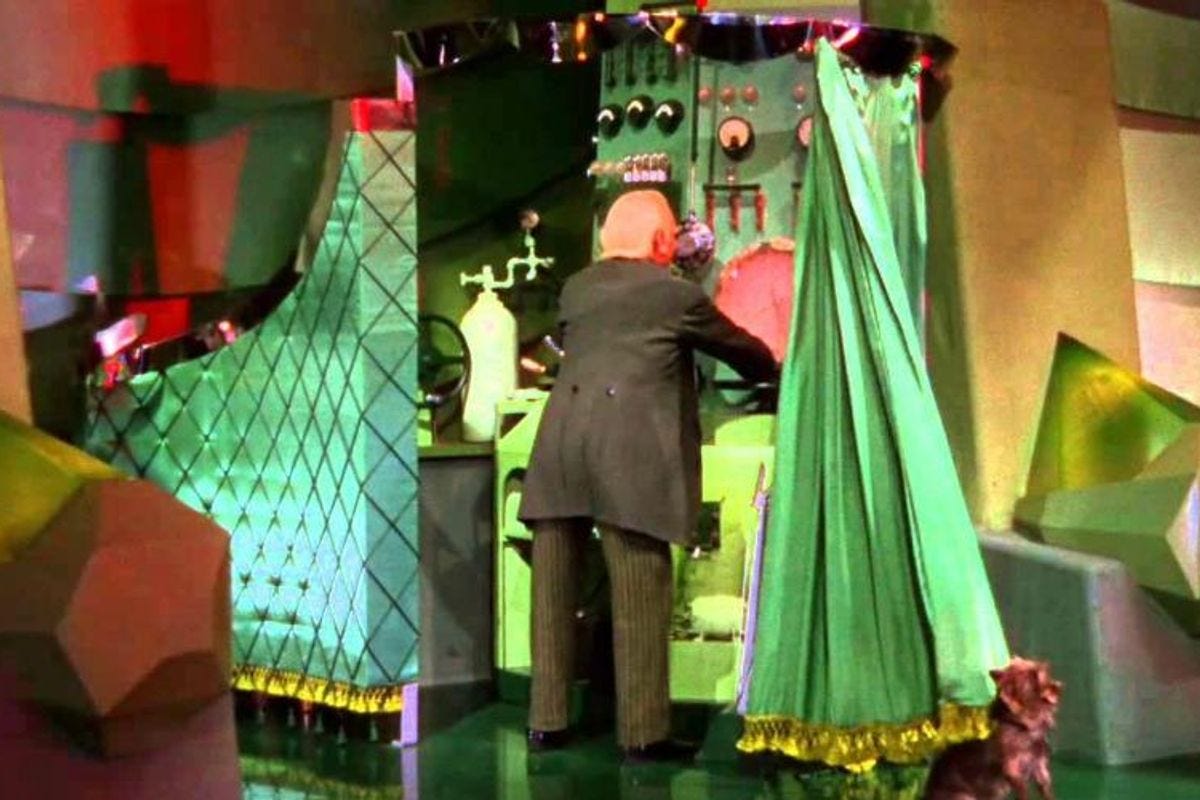

The Wizard of Oz demo

The Wizard of Oz demo is less fixed. We call this the “wizard of oz” demo because someone might be offstage actually doing some of the functions that the product will do. This is a great approach if you have some of the product solutions functioning and want to show them while others are yet to be developed.

If the investor believes that the “Wizard of Oz functions” are not high risk and doesn’t doubt that you can do them, this is a great way to demo. Why spend time on building something that everyone already knows can be built? If, however, the Wizard of Oz functions are difficult and high risk, you likely will not have an impressive demo.

Let’s use Lyft as an example again. If the CEO was giving a demo that showed drivers on a GPS and the cost of the drive estimated and presented by a team member on a computer in the background, no one would have complained. Of course, this could have been scripted, but the CEO was perhaps trying to show that the cost could be estimated in real-time - but wasn’t yet built.

The live demo with only your fingers on the keyboard

The live demo with only your fingers on the keyboard is impressive if you are trying to demonstrate that you’ve come up with a solution to a market problem but that the demo is only functioning on a limited basis. Why do you need your fingers only? Because if the investor had control of the keyboard, he would likely make choices out of the space that you’ve designed the demo. You know best what choices to make, and you can restrict the investor to them without having difficulties.

Using Siri as an example again, when we first were seeking funding, we were able to show how Siri worked on a limited set of questions in the market space of travel and entertainment. We knew in advance which questions would work and which would fail. We explained to the investors what we were trying to do and explained that we would be able to expand our capabilities in the near future - that what we were showing was not a fundamental limitation - only a current state of our development. But we gave the investors a choice of what they would ask, and we then asked those questions.

Live Demos of this type also enable “role-playing”. For example, when Jeremy Burton was demonstrating Wonolo to investors, one of the team would be the worker (Wonoloer), one of the team would be the customer, and one would be the administrator behind the scenes. Each person would announce their role and describe what they are doing, "I am the Wonoloer and I am looking for a job tomorrow" - basically verbalizing the user story. This demo was very powerful.

The live one-Inch demo

I’ve named this demo type “The live one-inch demo” because of how I first saw it used. In 1992, SRI and a team called the “Grand Alliance for HDTV” was leading the development of HDTV in the United States. The FCC had mandated that the new HDTV standard was going to be all digital. We were racing to prove that it was possible to take an HDTV signal which was a gigabit a second and compress it to 20 megabits per second - a 50X compression. Glenn Reitmeier at SRI and many others led this initiative, and developed the HDTV compression system they believed would work.

In order to demonstrate whether the compression technology worked, the team had to build an HDTV system, apply the compression technologies, and display the results of an HDTV video on the TV. Then they would review the results and see if there were any artifacts or other difficulties. The problem was that it was hugely expensive to demonstrate this on the full width of the television screen. Then one of the engineers came up with a genius solution: let’s just demonstrate it on one inch of the screen! That’s enough to prove that it worked!

As a result, the team was able to visually see any artifacts that existed. The results were outstanding. And the standards that SRI and the Grand Alliance developed for HDTV are the standards being used today.

The live demo with no constraints

If you’ve been so fortunate as to have developed a product, and you can show it live, this is the best possible situation for you. It is the most impressive. It demonstrates that you have already succeeded in solving the hard problems that you mentioned in the framing of the demo.

This situation might occur, for example, in a later stage of a venture. You should follow the guidance above on framing the story and hand the demo over to the investors. Let them use the system. Explain the bounds of its functionality. Expect that they will try hard to “break” it. Expect that they will go beyond the bounds. Try to make sure it fails gracefully.

As an investor, I’ve always enjoyed this type of demo because of its powerful impact. But one caution: when given this opportunity, I’ll always attempt to make it fail. If it fails for good reasons, it’s not a problem at all. But if the demo fails because it wasn’t able to perform as the presenter described, it would be a strong reason to pass on the opportunity.

I was once reviewing a venture that was developing a virtual assistant for education. The virtual assistant might enable a student to ask questions about a subject, and it would give the answer.

As an example, if a student were reading my book, “If You Really Want to Change the World,” and had a question as to how to make a venture presentation, the virtual assistant would find the information in the book and give a summary of how to make a venture presentation. The venture was using GPT-3 and claimed to be able to do this type of analysis. The team offered me to be a user and do a live demo. I was impressed - it answered some of my questions accurately and quickly. But then it began to fail on others.

And so my question to them became, can you construct a virtual assistant in education that sometimes gives the correct answer and sometimes not? Maybe. This was a hard problem.

This is a revised and updated post of the post originally on Platform Venture Studio.

If you like this post, please share it with others. I enjoy helping founders create great companies.

Your Venture Coach,

Norman

I love all the tech history in this! So interesting

Brilliant article. Thank you Norman!