Today, I offer you two versions of this post: a concise one for those of you who prefer key points and a longer one, delving into my personal journey and why I believe so strongly in how we measure our success.

The Concise Version

There are many people in this world who measure their success by the wealth they have earned, by the prestigious schools they went to, by their media praise, or by the awards they have accumulated. This pervasive egotism is increasingly evident today in realms like politics, business, and academia, and permeates our society.

These people are not the true greats. The true greats are the people who uplift others, helping them achieve what once might seem impossible. They are the people who recognize value in others and give of themselves to help nurture it. And that is the real measure of their success.

I have been privileged to be mentored and taught by many of these people. And one reason I deeply love Silicon Valley is that there has been a culture of helping others, without expectation of personal reward. It is a culture of “pay it forward.”

Pericles said it well: “What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.”

If you have been fortunate, your greatest contributions and value are not the measure of your wealth. They are the impact you make in enriching the lives of others.

The Longer Version (with my personal experiences)

Any success that I have had in life has been due to great people who helped me, mentored me, and taught me.

We don’t just “stand on the shoulders of giants,” like Isaac Newton once said. The giants I am speaking of lift us, and they put us on their shoulders.

My purpose in writing this post is not so much to tell my story as to bring to life how important it is to help others.

A Personal Journey

When I was 16, I lived in Newark NJ, and was a junior in a private school called Newark Academy, in Livingston NJ. My father was a self-made entrepreneur and ran a photography business with many photographers, buildings, cars, and equipment. We were a middle class family living in a middle class neighborhood of Newark NJ. Suddenly on March 2, 1964, my father, 54 years old, died of a heart attack.

Days later, my family lost everything. My father had let his life insurance lapse. His business fell apart. Everything was gone. Then, the IRS decided to audit, and my mother was a co-signer of the tax return. They estimated a huge tax bill, and threatened to charge her with fraud if she appealed. They took everything we owned except for a rundown photography storage building in downtown Newark. I remember standing in my driveway when the house was sold, with the IRS agent next to me, ready to receive the check. We now officially had nothing but the storage building.

The remaining part of that year I lived in the heart of downtown Newark, during the riots. My room was on the second floor of the storage building, next to the photography equipment. There was no kitchen, so I lived on tv dinners cooked in a microwave. There was a sink and toilet downstairs, but no shower. I had no desk, but my mother gave me a wood board to put on my lap and do my homework on.

My mother couldn’t afford to pay my tuition at Newark Academy for my next high school year, and we applied for a scholarship. They refused. It was a time of real angst. I knew I couldn’t keep living in the storage building.

My best friend was Greg Cherlin, who also loved mathematics, and was a true genius. Greg went to Weequahic High School in Newark, and applied to and was accepted at Yale University at the end of his sophomore year of high school. So I decided to try to do the same - skip my senior year completely, and apply to college at the end of my junior year.

I applied to the great schools I had originally hoped to attend if I had reached my senior year - Stanford, MIT, Cal Tech, Princeton, and a few other places. I was rejected by all but one, and told to apply again when I graduated high school. I was accepted on a scholarship at Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland Ohio, even though I had no high school degree, and am forever grateful to them.

After a year at Case Western Reserve, I was certain that mathematics was the subject I most loved, and decided to transfer to a university that was a leader in that field. My first acceptance letter came from my top choice: M.I.T. It was a dream come true. But there was no financial aid letter. I panicked and called the Dean of Admissions. The Dean said that I was indeed accepted, but they had a policy of not “pirating” students straight from other universities. I wouldn’t be able to get financial aid until my second year there. I begged him to reconsider but I had no success.

My next acceptance letter came from the University of Chicago (UofC). Again, there was no scholarship information. I had already told Case Western Reserve that I was planning to leave, and the Dean of Students told me they would take away my scholarship the moment I sent transcripts to other universities. That would enable them to offer the scholarship to others. Without a high school degree, and no college to go to, I was about to become a high school dropout.

I called the Dean of Admissions at UofC. He told me that not only was I accepted, but I would also soon get a notification that I would receive a full scholarship for the entire four years, contingent on my maintaining a high-grade point average. Knowing what happened with M.I.T, I asked him whether this might have been a mistake and that perhaps they also had a policy against pirating students away from other institutions.

His response was a hearty laugh: “We’re perfectly happy to pirate great students away from other institutions!” At that moment, I felt the incredible relief of knowing that I would be able to go to a great institution, and that the University of Chicago was a very special kind of University.

At UofC, I began to be helped by great professors, who only cared about giving me a chance to do whatever I wanted to do in life. These people never spoke about how great or important they were. All they wanted to do was help this young kid from Newark if ever and whenever he needed help.

These were the greats.

The University of Chicago

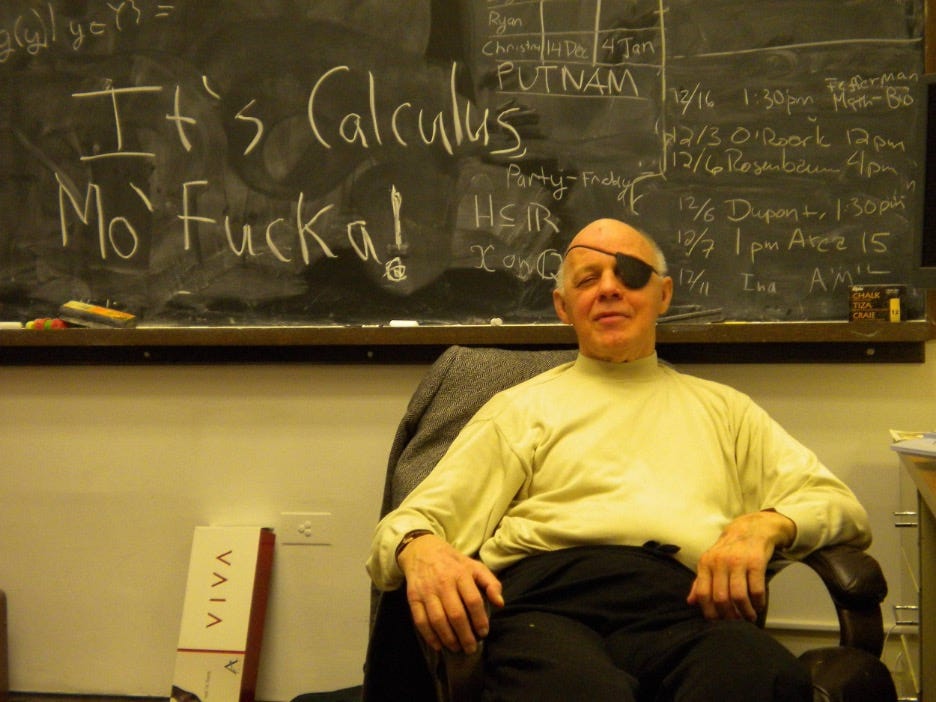

At the UofC, Izaak Wirszup, a Professor and a holocaust survivor, was a resident advisor at one of the dorms. He and his wife Pera hosted many small parties for undergraduates, with world-famous professors who spoke about exciting topics in their fields. I always showed up, and the Wirszup’s practically adopted me. Pera would stuff small sandwiches into my pockets. Izaak introduced me to both the great mathematicians and to his own love of mathematics. Even after I graduated, we kept in touch for decades.

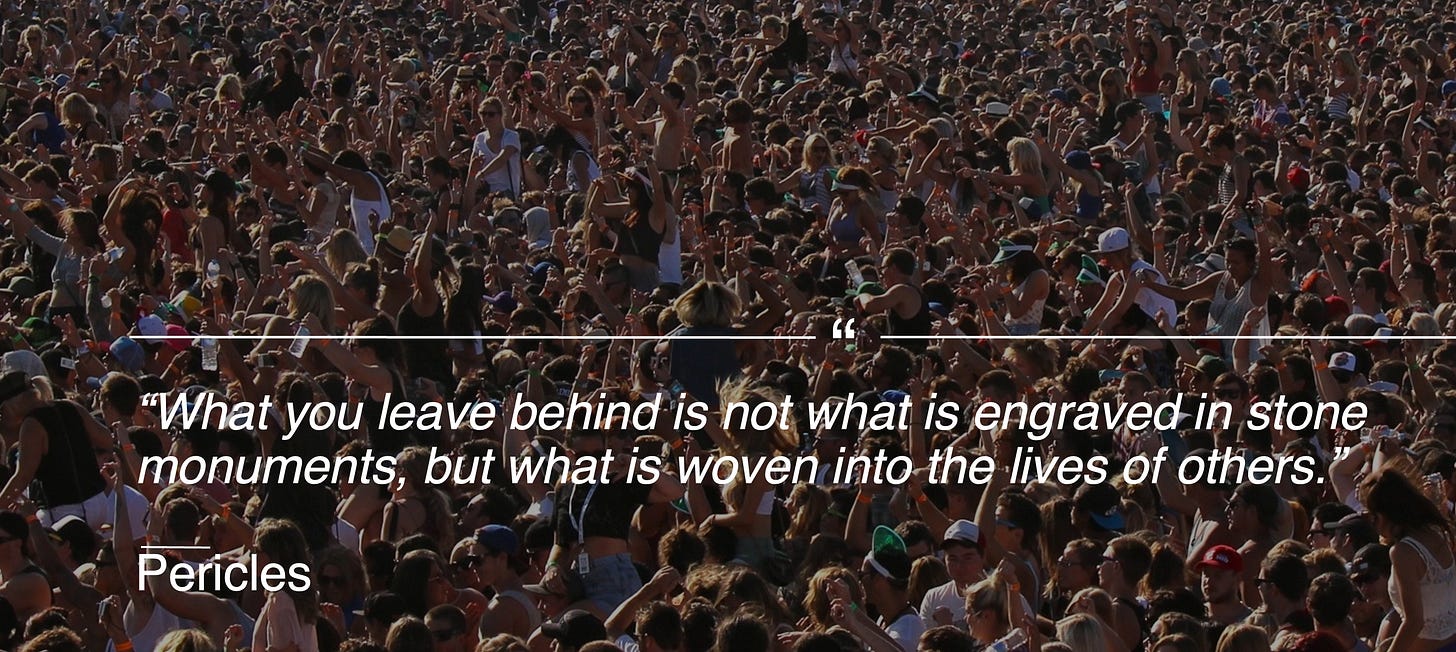

I loved the way mathematics was taught at Chicago. For example, my first classes were not just about solving equations. They were about the fundamental principles of mathematics. I remember that my first class in Calculus, taught by Paul Sally, began by constructing the real number system and then deriving all its attributes from first principles.

Paul, a full professor at Chicago, took me under his wing from almost my first days at Chicago. He mentored me and taught me the depth and beauty and simplicity of mathematics.

Paul also taught me the importance of giving back. In his spare time, he taught math on weekends to inner-city Chicago youth, and wrote several introductory books on mathematics. He was also a co-founder of the “Chicago Math” program.

I graduated from Chicago and went on to graduate school there, getting my Ph.D. with Paul as my thesis advisor. Then, while at Chicago, Paul and I were invited to spend 2 years as visiting members at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. We arrived in June of 1971.

The Institute for Advanced Study

To my mind, the permanent members of the Institute were the greatest mathematicians and physicists on the planet. This was the original place of Einstein, Oppenheimer, Von Neumann, Godel, Andre Weil, Andrew Weyl, Harish-Chandra Mehrotra, Freeman Dyson, and more.

At the Institute, there were no classes. They offered no degrees. There were no requirements. I was invited to spend 2 years there, studying my field of mathematics called Harmonic Analysis. Most days, there were lectures by the great mathematicians and physicists on their current research. They lectured on whatever they wanted to. Whatever interested them. And we would learn.

What shocked me at the Institute was how they freely shared their wisdom. Every day, lunch would be served, and all the visitors and members would eat together in the dining hall. The physicists were at one table, the number theorists at another, the harmonic analysts at another. And we would learn together, talk together, brainstorm together.

Often, we took walks together in the grassy field, around the lake, and into the woods, and discussed our research problems. Then, at 3pm, tea would be served in the main room downstairs. This was a beautiful room with plenty of space for sitting and talking together. It also had newspapers in many languages from many countries in the world. Almost everyone would come for tea and conversation. And then we would go back to our offices, and continue our work.

What I learned from them, more than the mathematics, was their humility, their hard work, their passion, and their way of thinking. The people I worked with were not egotists. They shared freely of their knowledge. They explained their work in a way that was clear and simple, not complex. They were generous with their time and energy. They worked long hours. And they were always willing to talk with the young newcomers, who had not yet anything like their successes.

I have to admit that ever since I was at the Institute, I felt I better understood the character, culture, and values of the “true greats.” They were not egotistic. They were not so much enchanted by their own successes as by their desire to work together with others to explore and create new ideas. They were eager to “give back” and help the new young mathematicians. They were eager to hear our stories and our ideas. Conversations weren’t about what they had done. It was about their asking what others were doing. And they were always offering to help.

RCA Laboratories

After leaving the Institute, I decided that I wanted to work in applied mathematics - the type of mathematics that would have an impact on important problems in our world today. I joined RCA Laboratories, and I again had a chance to work with great scientists and engineers who took me under their wings. Roger Cohen, Ralph Klopfenstein, Roger Crane, and Curt Carlson taught me everything I learned. Our only goal was to work together to accomplish great things. We never spoke about who would get credit or blame. We never discussed what value we might receive. We only discussed breakthrough ideas.

And then, after RCA Laboratories was acquired by Stanford Research Institute (SRI), we decided to create ventures from the technology we created. Again, we started from nothing. We had no idea how to create and build ventures. But great VCs such as David Liddle, Yogen Dalal, Gary Morgenthaler, Vinod Khosla, and David Ladd taught us everything. When we first began, we didn’t have a great portfolio of ventures for them to invest in. But we had great technology and great people, and a desire to learn.

The companies we created, such as Siri, Nuance, Orchid Biocomputer, Intuitive Surgical, and many more, would almost certainly never have happened without them.

Any value that I helped create in my lifetime is entirely attributable to the professors, mentors, business partners, and VCs who helped me along the way. If credit is to be given, they deserve it.

My whole point in this story is that the real measure of our success isn't what we ourselves achieve. It is the value we create by helping others. That is our true mission in life. That is what I hope you will do when others might benefit from your help.

Your Venture Coach,

Norman

That’s a great story, Norman, thanks for sharing! I also owe much of where I am today and the many things I had the opportunity to see, do and learn throughout my life to a number of people who enjoyed giving back and found their own success in seeing others succeed. And I try to honor them by doing the same where I can.

“It’s easy to make a buck. It’s a lot tougher to make a difference.” – Tom Brokaw

Great you wrote this down for your family. And -- important points.