This story is an adaptation of a eulogy I gave in 2008 for Izaak Wirszup, a mentor who changed my life.

In 1964, at 16 years old, I was navigating a world of loss and uncertainty. My father died suddenly with a heart attack at the age of 54. He somehow let his life insurance lapse, and on top of that, the IRS audited his photography business and claimed that we owed a great deal of unpaid taxes. They threatened my mother, a co-signer of the tax return, with fraud charges if she appealed. And so the IRS took our home, our car, our savings, and everything else we owned - except a single photography studio/storage building in Newark, N.J.. There, my mother and I lived on the second floor, with cots next to the photography equipment. Our only income was social security.

I couldn’t continue living that way, and I decided to leave high school at the end of my junior year. I applied to college, and Western Reserve University (now called Case-Western Reserve University) saw past my lack of a high school degree, admitted me, and gave me a scholarship. After a year there, I decided to try to transfer to one of the schools I had always dreamed of going to: MIT, the University of Chicago, Stanford, or Princeton. MIT was my first choice.

When the universities sent out their decisions to the applicants, I was excited to receive the first letter from MIT. I was accepted! But there was nothing mentioned about the scholarship I applied for.

I called the Dean of admissions and asked if I would be receiving a scholarship. The Dean said MIT had a policy of not pirating students from other universities, so I would not be eligible for a scholarship that year. I pleaded with the Dean, explaining I had no other means to attend. He wouldn’t budge.

The next acceptance letter came from the University of Chicago. Again, I was overjoyed to be accepted, but nothing about scholarship was mentioned. With real dread, I called the Dean of admissions and asked if I would be receiving a scholarship. I said that I had just had a conversation with the Dean of Admissions at MIT and was told about the “anti-piracy” policy. Would he have the same policy?

The Dean let out a roar of laughter. He said that the University of Chicago is perfectly happy to pirate students from other universities! And yes, he confirmed that I would be receiving a scholarship for the four years I was there as long as I maintained a high GPA. This conversation with the Dean and the superb reputation of the physical science division at the University convinced me immediately that the University of Chicago was the one I wanted to attend.

And so, in 1966, I arrived at the University of Chicago on a scholarship, alone, intimidated, and unsure of my future.

Then I met Professor Izaak Wirszup.

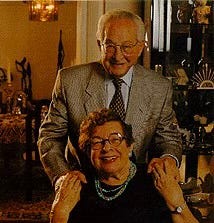

At first, I knew Izaak as the voice of passion behind his lectures about the poor state of mathematics education in the United States. Later, I encountered him and his wife, Pera, as the resident faculty members at Woodward Court, where they sponsored the Woodward Court Lecture Series. Going to these lectures in their home was like being invited to a famous parlor event with delicious appetizers, wine, and fine crystal glasses. Even though I was a young student, those evenings gave me the chance to talk with some of the greatest minds of the day. As I left, Pera would always find a way to discreetly tuck a few appetizers into my pocket. She would whisper, “Norman, you are too thin!”

I saw Izaak both at the University and at those lectures, and I felt as if Izaak and Pera had almost adopted me. When Izaak greeted me, it wasn’t just a hello - it was an embrace made of words. “Nooorrrmmmannn”, he’d exclaim, in his heavy Polish accent, with his voice booming with love, kindness, and enthusiasm. “Vveee are so happy to see you!” Then, he would ask me about my work and tell me how proud he was of me.

He didn’t stop there. Izaak took me under his wing, steering me toward the best professors and the most critical subjects in mathematics. Because of him, I was privileged to learn from the giants of mathematics in my field - like Antoni Zygmund, Alberto Calderón, Israel Herstein, and Paul Sally. He didn’t just help me shape my career in mathematics; he helped me find my calling.

Izaac would always remind me of my responsibility to do good for others, to do well for this country that had given us our freedom, and for this great university that has given us our learning and our livelihood. He reminded me of the global importance of mathematics and science and the need for the United States to maintain its leadership. Izaak did not just speak about this. He acted by testifying to Congress, by helping develop new funding sources to create new curricula, and by creating the curricula as well. And always, he would speak of the University of Chicago as the best place in the world.

Sometimes, in a rare moment, Izaak and Pera would share with me some of their personal history as holocaust survivors. Both Izaak and Pera lost almost all their families, including their spouses and Izaak’s young son. Pera and her daughter Marina survived. Talking with Izaak and Pera about the unimaginable trauma they experienced gave a new meaning to the word “survivor” for me. It did not need to mean that they merely were able to continue their existence, though they had been so terribly hurt. “Survivor” could mean that they had lived through the most evil events but that now, they could still be gentle, show love and kindness to everyone, enjoy every moment of life, and achieve greatness. This is a great lesson in life.

I kept in contact with Izaak and Pera during the following years and after receiving my Ph.D. in mathematics at the University of Chicago. Izaak and Pera were always interested in and loving to my family. It was a great joy to call Izaak and tell him when I was given the chance to lead the Special Committee of the Dean of the Physical Science Division at the University of Chicago.

Each of us is fortunate in our lives if we find just one teacher who has been interested in us, who has given us guidance and support, and who has a passion for our chosen field. Izaak didn’t just do all those things. He and his wife, Pera, reached out to me and my family with radiating warmth and love. And by doing this, his impact on the special events and choices that shaped my career, my view of life, and my love for the University was absolute.

Here is the part that might be hard for you to imagine. Multiply my story by tens, maybe hundreds, or possibly thousands of students whose lives and careers Izaak have enriched. That is Izaak’s legacy that will go on forever.

Thank you, Izaak, for showing me what real mentorship is, and for your gift of love and kindness. You are with us always.

My point in this post is that Izaak understood the essence of mentorship. It is not just about coaching or imparting knowledge. It is about seeing people for who they are, believing in their potential, and nurturing their growth. Mentors like Izaak don’t just shape careers; they shape lives.

As I reflect on Izaak’s legacy, I am reminded of how vital it is for each of us to pay it forward. Whether we are founders, leaders, or teachers, we all have the power - and the responsibility - to be that guiding voice, that warm welcome, or that critical push. The kind of mentor who helps shape lives.

And the best way to honor the mentors who helped shape us is by becoming one ourselves.

Your Venture Coach,

Norman

Thanks for sharing, Norman. Your experience gives a different yet integral definition about mentorship.

Thank you for sharing this. This is an important example, not only of mentorship, but also the importance of caring and loving of others. Clearly a good mentor not only provides guidance, but love and support , allowing confidence in one's success. - Mike Leopold